Raverat blog Archive for April 2014

|

By William | 7 Mar 2018 08:00:00 |

Archive for April, 2014

A presentation given at the

Cambridge Literary Festival

on April 6th, 2014

in the Winstanley Lecture Theatre, Whewells Court, Trinity College

by William Pryor with the actress Anne Harvey

William: In the preface to her masterpiece of a childhood memoir, Period Piece, my grandmother, Gwen Raverat makes it clear that:

Anne: This is a circular book. It does not begin at the beginning and go on to the end; it is all going on at the same time, sticking out like spokes of a wheel from a hub, which is me. So it does not matter which chapter is read first or last.

William: So will this divertissement be circular; the spokes of my narrative jumping out in all directions. We’re going to talk about Cambridge, childhood, Charles Darwin, Gwen Raverat, Vaughan Williams, her art, Trinity College, her writing, Virginia Woolf, various species of bohemia, what it is to be a Darwin and more.

I grew up in Cambridge, went to Kings College Choir School. My father was Senior Tutor at this very college. My childhood was lived on my bike and in the summer on the river. Cambridge, particularly Barton and Chaucer Roads, Coe Fen, what is now Darwin College and, of course, Trinity College, which has admitted dozens of Darwins and Pryors (including me) to its hallowed halls, all this evokes the pent-up smells and memories of my childhood. Just as Down House, Silver Street, the Backs, the Cam and Newnham Grange did for my grandmother.

As a Darwin in genes and memes if not in surname – the great god of science was my great-great-grandfather – I have always been torn between promoting my evolutionary genes and keeping quiet for the sake of Anglican modesty. The former has usually won and continues to do so when I prattle on about my grandmother, Gwen Raverat’s life and art.

Before we go any further I should lay out the genealogical geography. Charles Darwin and his wife Emma (née Wedgwood) had ten children, seven of whom survived childhood. (There are now at least 210 direct descendants with evolutionary blood in their veins). Charles Darwin’s fifth child George was knighted and was both a Fellow of this establishment (as were his brothers Francis and Horace) and of the Royal Society and Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy. He married an American, Maud du Puy, from a Philadelphian family of Huguenot descent, when she came hunting a husband to Cambridge in 1883.

Despite her preface, Gwen opens the first chapter or Prelude of Period Piece right at the beginning:

Anne: In the spring of 1883 my mother, Maude Du Puy, came from America to spend the summer in Cambridge with her aunt, Mrs. Jebb. She was nearly twenty-two, and never been abroad before; pretty, affectionate, self-willed and sociable; but not at all a flirt. Indeed her sisters considered her rather stiff with young men. She was very fresh and innocent, something of a Puritan, and with her strong character, was clearly destined for matriarchy.

William: They married a year after Maud’s husband-hunting trip (I wonder where the writer of Downton Abbey got the idea of an American lady hunting for respectable marriage to an English Gentleman?). They bought and renovated the building they named Newnham Grange, now Darwin College. They had five children, four of whom survived. George’s firstborn was Gwendolen Mary Darwin. She married French painter Jacques Raverat in 1911. They had two daughters: Elisabeth, who married the son of the Norwegian Prime Minister in 1940, and my mother Sophie who married the entomologist Trinity don, Mark Pryor. They had 3 daughters and me.

And the family tradition continues: my youngest sister, Nelly married Philip Trevelyan, cousin and fellow great-great-grandchild, the grandson of George’s younger brother Francis. Gwen had two brothers and a sister: Charles, Margaret and Billy, in that order. Margaret married Geoffrey Keynes, surgeon brother of Maynard, the economist, builder of the Arts Theatre and Bloomsbury stalwart.

You begin to get a glimpse of the Cambridge-centric network that is the Darwin family, in the middle of which Gwen grew up. A web that was greatly extended by the Wedgwood, Keynes, Du Puy, Cornford, Barlow and other families they married into. When travelling, there was hardly a major city that didn’t have a Darwin one could stay with. It all fed into a pronounced Darwinian noblesse oblige

Gwen’s father George Darwin was once infuriated by the non-delivery of a telegram addressed ‘Darwin, Cambridge’, as a result of which Maud had missed seeing one of her sisters before her return to America. When the post office explained that he was not the only person named Darwin residing in Cambridge, and the lack of forename or initial had made it impossible to know for whom it was intended, George was so incensed he wrote a letter of complaint to The Times. Emma Darwin sympathised with him and wrote to her daughter-in-law Maud:

Anne: How vexatious it was about the telegram… If Darwins are not known at Cambridge where are they to be heard of?

William: The meme of privilege and authority peculiar to many Darwins pushed Gwen into the almost bohemian, parent-upsetting life of an artist. The same was true for me: let me illustrate with story from my youth. I was once commuting between Cambridge and London to do my A Levels and would ride my bike across the Cambridge shunting yards to get to the station. One day a British Rail employee stopped me.

Anne: “Ere, you, you can’t ride across here,”

William: he said from beneath his PVC cap.

“That’s quite alright my man,” I replied, “I’m a Darwin and a member of the British Empire.”

Anne: “Oh, sorry sir, didn’t realise.”

William: He replied, tipping his forelock as he waved me on my way.

Or earlier, when being frog-marched through the Bible by my unbelieving parents so I could pass the Divinity paper of the Common Entrance exam for Eton, I discovered a glaring misprint. On one page this chap was called Saul, but on the next Paul. I proceeded to make helpful corrections with my biro.

But back to that solid web of Darwins: Gwen writes wonderfully about her uncles in Period Piece. Her Uncle Francis, or Frank, married three times. His second wife Ellen had one child, a daughter, Frances with an “e”. A fine poet, Frances, confusingly, married Cambridge classics don Francis Cornford. She was Gwen’s best friend and Period Piece is dedicated to her. Later, Gwen and Frances wrote a play: The Importance of Being Frank. In The Five Uncles chapter, Gwen writes:

Anne: Uncle Frank was the only one of the brothers who was a naturalist. My father or Uncle Horace would notice the ripple-marks in the sea-sand, or the way in which the deep pot-holes in a worn road were formed; or they would notice that an obsolete wooden plough was still in use; but neither of them—none of them except Uncle Frank—noticed ‘birds and beasts and flowers’; though Uncle William knew something of geology. But Uncle Frank was a real field naturalist, making botany his chief study, but knowing a great deal about birds as well. He became his father’s assistant at Down, and his father said once, when they were collaborating on a paper: ‘Frank works too hard, he’ll never get on.’ In a way this was true; he would work for ever on a subject, but he had little ambition, and hardly cared at all for the honours that came to him.

The Cornfords’ second child, John, a communist and poet, died in the Spanish Civil War. John’s son, James was then brought up by Frances. Their third child, Christopher, became Head of the Department of Humanities at the Royal College of Art. (I feel we could establish a degree course in Darwin Progenical Dynamics!)

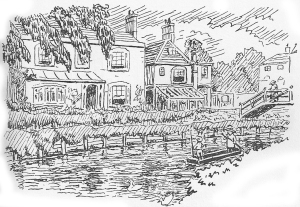

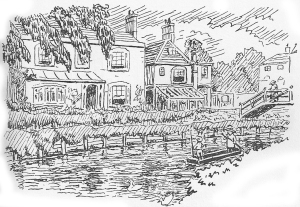

Gwen writes of her early experience of Newnham Grange in Period Piece:

Anne: My mother took to it [the house and the river] with enthusiasm, which was characteristically brave of her; for most mothers would have thought the situation damp, and the river both dangerous and smelly.

And so it was; I can remember the smell very well, for all the sewage went into the river, till the town was at last properly drained, when I was about ten years old. There is a tale of Queen Victoria being shown over Trinity by the Master, Dr. Whewell, and saying, as she looked down over the bridge: ‘What are all those pieces of paper floating down the river?’ To which, with great presence of mind, he replied: ‘Those, ma’am, are notices that bathing is forbidden.’

William: And here we are today in Dr Whewell’s Court, where I lodged in my first year reading what was then called Moral Sciences under the appropriately named Professor Wisdom. You can read of my bohemian days in Whewells Ct as a beatnik undergraduate in my memoir, The Survival of the Coolest.

But Period Piece is perhaps the best childhood memoir ever written and this early paragraph about Gwen’s childhood at Newnham Grange epitomises her magical powers at evoking a Victorian childhood, indeed any childhood:

Anne: From the big night nursery window we could look right down on to the slow green river beneath us; and if a boat went by it was reflected upside down, as a patch of light moving across the ceiling; and the ripples always purled in a dancing rhythm there, when the sun shone. Across the Little Island we could see up to the weir and the footpath along the Upper River, where I always thought the Lord walked when he led his flock to lie down in green pastures. Here we were never out of hearing of the faint sound of the water running over the weir; and on windy winter nights, when we were in bed, we could hear, a long way off, the trucks being shunted at the station and the whistling of the engines on the line. That was when you couldn’t sleep because you had a ‘feverish attack’ and, wonderfully, there was a fire in the night nursery, throwing up the flickering criss-cross of the high fender on the ceiling; and you were glad to be safe in bed, because of the lonely dreadfulness of the night outside. And in the dark early morning we could sometimes hear from the Big Island the crowing of the cocks, which disturbed my father so much.

William: Those sounds were also part of my childhood: the shunting trains, the sound of water. Talking of sounds, before we delve further into my grandmother’s childhood, life and prodigious artistic achievements let me explain why we played that particular music at the beginning. It was composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams for the ballet Job, a Masque for Dancing, for which Gwen designed the sets and costumes.

Gwen’s brother in law, Geoffrey Keynes, brother of Maynard, had for many years been an aficionado of William Blake’s engravings while Maynard’s passion for the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova and their wedding in 1925 increased Geoffrey’s interest in making a ballet based on Blake’s Job engravings which he thought one of his masterpieces.

Geoffrey asked for Gwen’s help. They constructed a scenario which Gwen then translated into French so it could be submitted to Diaghilev. She talked to her cousin Ralph Vaughan Williams (his grandmother was Darwin’s sister) and, though not a ballet enthusiast, he agreed to write the music. Meanwhile Gwen had made designs for backdrops and miniature cardboard figures for each scene (now in the Fitzwilliam).

When the Ballets Russes turned it down Vaughan Williams immediately began turning the music into a concert suite. Gwen’s cardboard theatre was the saving of the project as a ballet when Lilian Bayliss and Ninette de Valois were shown it. Coming as it did after the end of the Ballets Russes, Job was regarded by many as the first truly English ballet.

Let us not forget that Gwen came to write Period Piece at the end of a long and fruitful life in which she cut some 590 wood engraving images, painted maybe 100 paintings, wrote extensive art criticism and dashed off Period Piece when in her sixties. All the art is now managed by the Raverat Archive – the wood engravings can be seen at Raverat.com.

One of the wonders of Period Piece is the array of aunts and uncles and the way Gwen conveys their absurdities but never to denigrate them. The star aunt is definitely Etty, as evidenced from this excerpt from the chapter dedicated to her:

Anne: I have been told that when Aunt Etty was thirteen the doctor recommended, after she had a ‘low fever’, that she should have breakfast in bed for a time. She never got up to breakfast again in all her life. I admit that I know none of the facts, but I cannot think it good mothering on the part of my grandmother to have allowed a child to slip into such habits. Anne: I have been told that when Aunt Etty was thirteen the doctor recommended, after she had a ‘low fever’, that she should have breakfast in bed for a time. She never got up to breakfast again in all her life. I admit that I know none of the facts, but I cannot think it good mothering on the part of my grandmother to have allowed a child to slip into such habits.

The three of her children who were most affected by the cult of ill-health, were Aunt Etty, Uncle Horace, and, later on, my father, George, though as a boy he was strong enough. But illness, real or imaginary (and there was certainly both), did not prevent my father and Uncle Horace from doing a great deal of work. Unfortunately Aunt Etty, being a lady, had no real work to do; she had not even any children to bring up. This was a terrible pity, for she had nothing on which to spend her unbounded affection and energy, except the management of her house and husband; and she could have ruled a kingdom with success. As it was, ill-health became her profession and absorbing interest. But her interest was never tinged by self-pity, it was an abstract, almost scientific interest; and our sympathy was not demanded. She kept her professional life in a separate compartment from her social life.

She was always going away to rest, in case she might be tired later on in the day, or even next day. She would send down to the cook to ask her to count the prune-stones left on her plate, as it was very important to know whether she had eaten three or four, prunes for luncheon. She would make Janet put a silk handkerchief over her left foot as she lay in bed, because it was that amount colder than her right foot. And when there were colds about she often wore a kind of gas-mask of her own invention. It was an ordinary wire kitchen-strainer, stuffed with antiseptic cotton-wool, and tied on like a snout, with elastic over her ears. In this she would receive her visitors and discuss politics in a hollow voice out of her eucalyptus-scented seclusion, oblivious of the fact that they might be struggling with fits of laughter. She characteristically wrote to a proposed visitor: ‘Don’t come by the ten o’clock train, but by the 3.30, so as to give me time to put you off, if I am not well’. In the year 1920, when she was seventy-seven, one of her little great-nieces happened to get chicken-pox in her house. Aunt Etty wrote to Charles at Cambridge, asking him to look in the Down family Bible to find out whether she had had the disease herself, as she did not want to catch it. He was not able to find the Bible at once—it was in a box at the bank—so she wrote again, very urgently. Upon which he had the satisfaction of replying by telegram: ‘ Yes, you had chicken- pox in August 1845.’ (All the illnesses and vaccinations are carefully recorded in the Down Bible, but it does not look as if it had been much used for anything else.)

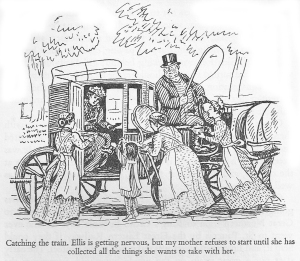

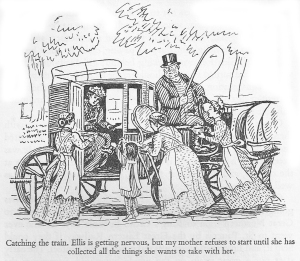

William: There are definitely Darwinian genetic traits apart from hypochondria, not least the tendency to make mountains out of minor mole hills. Take this account from Period Piece which could so easily be describing the gritted-teeth approach to family fun and frolics I experienced in my youth 60 years later:

Anne: It was a grey, cold, gusty day in June. The aunts sat huddled in furs in the boats, their heavy hats flapping in the wind. The uncles, in coats and cloaks and mufflers, were wretchedly uncomfortable on the hard, cramped seats, and they hardly even tried to pretend that they were not catching their deaths of cold. But it was still worse when they had to sit down to have tea on the damp, thistly grass near Grantchester Mill. There were so many miseries which we young ones had never noticed at all: nettles, ants, cow-pats. . . besides that all-penetrating wind. The tea had been put into bottles wrapped in flannels (there were no Thermos flasks then); and the climax came when it was found that it had all been sugared beforehand. This was an inexpressible calamity. They all hated sugar in their tea. Besides it was Immoral. Uncle Frank said, with extreme bitterness: ‘It’s not the sugar I mind, but the Folly of it.’ This was half a joke; but at his words the hopelessness and the hollowness of a world where everything goes wrong, came flooding over us; and we cut our losses and made all possible haste to get them home to a good fire.

William: Through their fathers’ friendship, Gwen got to know Virginia Woolf, née Stephen, when she won her parents approval to become one of the first women to study at the Slade School of Art, in London. Gwen joined the Stephen sisters’ Friday Club, the beginnings of the Bloomsbury Group, and soon became its secretary. Through them she met Rupert Brooke and the other Bloomsberries. The romance of their bohemian attitude to art and love had its effect on Gwen, though it would never dominate her.

There was a moment, no doubt under the spell of the Stephen sisters, that Gwen thought she might just be a writer. She started a novel. It wasn’t very good, but does convey that bohemian spirit, nay meme, that has also driven much of my life. She could be writing of my teenage years of intense, dope-filled beatnikery:

Anne: We met, we found we had many ideas in common; we found that we could talk. And so we talked from morning to night and from night till morning, and for the first two years we did practically nothing else. We had been shy and diffident; we had wondered if anyone had ever had such ideas as ours before; we had wondered if they could possibly be true ideas; if there was the remotest chance that we could be worth anything. …..

I remember those first two years as long days and nights of talk; talk, lying in the cow parsley under the great elms; talk in lazy punts on the river; talk round the fire in Rupert’s room; talk which seemed always to get nearer and nearer to the heart of things. It was best of all in the evenings in Rupert’s room. He used to lie in his great armchair, his legs stretched right across the floor, his fingers twisted in his hair; while Jacques sat smoking by the fire, continually poking it; his face was round and pale; his hair was dark. We smoked and ate muffins or sweets and talked and talked while the firelight danced on the ceiling, and all the possibilities of the world seemed open to us.

For a time we were very decadent. We used to loll in armchairs and talk wearily about Art and Suicide and the Sex Problem. We used to discuss the ridiculous superstitions about God and Religion; the absurd prejudices of patriotism and decency; the grotesque encumbrances called parents. We were very, very old and we knew all about everything; but we often forgot our age and omniscience and played the fool like anyone else.

William: It was at Aunt Etty’s London house that Gwen’s love affair with wood engraving began – in particular with the doyen of 18th Century engravers, Thomas Bewick. She wrote:

Anne: It was [at Aunt Etty’s house] that I discovered Bewick, one afternoon while Aunt Etty was having her rest. I remember lying on the sofa between the dining-room windows with the peacock-blue serge curtains, and wishing passionately that I could have been Mrs. Bewick. Of course, I should have liked still more to be Mrs. Rembrandt, but that seemed too tremendous even to imagine; whereas it did not seem impossibly outrageous to think of myself as Mrs. Bewick. She was English enough, and homely enough, anyhow. Surely, I thought, if I cooked his roast beef beautifully and mended his clothes and minded the children—surely he would, just sometimes, let me draw and engrave a little tailpiece for him. I wouldn’t want to be known, I wouldn’t sign it. Only just to be allowed to invent a little picture sometimes. O happy, happy Mrs. Bewick! thought I, as I kicked my heels on the blue sofa. Anne: It was [at Aunt Etty’s house] that I discovered Bewick, one afternoon while Aunt Etty was having her rest. I remember lying on the sofa between the dining-room windows with the peacock-blue serge curtains, and wishing passionately that I could have been Mrs. Bewick. Of course, I should have liked still more to be Mrs. Rembrandt, but that seemed too tremendous even to imagine; whereas it did not seem impossibly outrageous to think of myself as Mrs. Bewick. She was English enough, and homely enough, anyhow. Surely, I thought, if I cooked his roast beef beautifully and mended his clothes and minded the children—surely he would, just sometimes, let me draw and engrave a little tailpiece for him. I wouldn’t want to be known, I wouldn’t sign it. Only just to be allowed to invent a little picture sometimes. O happy, happy Mrs. Bewick! thought I, as I kicked my heels on the blue sofa.

William: Gwen’s wood engravings are every bit as powerfully evocative as were her cousin Ralph Vaughan Williams’ later symphonies. His music, like Gwen’s art, was quintessentially English, lyrical, angry, tragic, startling, grand, mythic. In The Origins of the English Imagination, Peter Ackroyd writes: If that Englishness in [his] music can be encapsulated in words at all, those words would probably be: ostensibly familiar and commonplace, yet deep and mystical as well as lyrical, melodic, melancholic, and nostalgic, yet timeless.

A lovely description of why Gwen’s work engages so readily. Small though they are, her best prints (and there are many) are finely tempered expressions of a love of humanity and its landscape. Simon Brett writes in his postscript to the Silent Books edition of the catalogue raisonee of her work: The regard she turned upon reality – upon landscape, figures in landscape, sometimes the incidents of story – sees all things together. Her vision is to do with seeing (that is not as obvious as it sounds). In this primacy of seeing, interpretation, expression, storytelling or imagination are gathered up into statement: this is how it is. The ease with which the figures lie, at one with their being and the world around them, thereby stands comparison with the etchings of Rembrandt that were her childhood pillow-book, or with the idylls of Titian or Seurat.

Brett is echoing a point Gwen made herself. She wrote of wood engraving that it was

Anne: “hard, tight, definite” with “no possible room for vagueness”. It is the looking, the seeing that matters.

William: William Carlos Williams, when explaining his poetics, said that there are no ideas but in things.

But all this talk of Gwen’s creativity has wandered far from this morning’s subject: Period Piece and childhood. It is interesting that she wrote this about her Aunt Etty’s thoughts on “Great Men”:

Anne: An amusing recollection is of overhearing scraps of conversation about ‘that foolish young man, Ralph Vaughan Williams’, who would go on working at music when ‘he was so hopelessly bad at it’. This memory is confirmed by a letter of Aunt Etty’s: ‘He has been playing all his life, and for six months hard, and yet he can’t play the simplest thing decently. They say it will simply break his heart if he is told that he is too bad to hope to make anything of it.’ She held much the same opinion of the early writings of E. M. Forster, a family friend: ‘His novel is really not good; and it’s too unpleasant for the girls to read. I very much hope he will turn to something else, though I am sure I don’t know what.’ But, of course, these two were not great men then; this is what you have to go through to become great.

William: Elsewhere Gwen shows us the seeds of her artistic temperament when she writes about visits to her grandfather’s home at Down House:

Anne: But to us, everything at Down was perfect. That was an axiom. And by us I mean, not only the children, but all the uncles and aunts who belonged there. Uncle Horace was once heard to say in a surprised voice: ‘No, I don’t really like salvias very much, though they did grow at Down.’ The implication, to us, would have been obvious. Of course all the flowers that grew at Down were beautiful; and different from all other flowers. Everything there was different. And better. Anne: But to us, everything at Down was perfect. That was an axiom. And by us I mean, not only the children, but all the uncles and aunts who belonged there. Uncle Horace was once heard to say in a surprised voice: ‘No, I don’t really like salvias very much, though they did grow at Down.’ The implication, to us, would have been obvious. Of course all the flowers that grew at Down were beautiful; and different from all other flowers. Everything there was different. And better.

For instance, the path in front of the veranda was made of large round water-worn pebbles, from some sea beach. They were not loose, but stuck down tight in moss and sand, and were black and shiny, as if they had been polished. I adored those pebbles. I mean literally, adored; worshipped. This passion made me feel quite sick sometimes. And it was adoration that I felt for the foxgloves at Down, and for the stiff red clay out of the Sandwalk clay-pit; and for the beautiful white paint on the nursery floor. This kind of feeling hits you in the stomach, and in the ends of your fingers, and it is probably the most important thing in life. Long after I have forgotten all my human loves, I shall still remember the smell of a gooseberry leaf, or the feel of the wet grass on my bare feet; or the pebbles in the path. In the long run it is this feeling that makes life worth living, this which is the driving force behind the artist’s need to create.

Of course, there were things to worship everywhere. I can remember feeling quite desperate with love for the blisters in the dark red paint on the nursery window-sills at Cambridge, but at Down there were more things to worship than anywhere else in the world.

William: By 1920 Jacques had been diagnosed with Disseminated Sclerosis as MS was then known and they were advised to move to the South of France for his health. They moved to Vence, ten miles inland from Nice, the town that would later be Matisse’s home. Though they knew, without outwardly acknowledging it, that he was dying, their creativity was at its height. Gwen’s wood engravings and Jacques’ paintings were at their most eloquent. It was then that their relationship with Virginia Woolf burgeoned in an extraordinary exchange of letters.

In one to my grandfather, not long before his death, Virginia wrote this extraordinary paragraph that has become totemic for me: Is your art as chaotic as ours? I feel that for us writers the only chance now is to go out into the desert & peer about, like devoted scapegoats, for some sign of a path. I expect you got through your discoveries sometime earlier.

In 1924, stressed with looking after two small girls (my mother and aunt) and her dying husband Jacques, Gwen still felt it a matter of life and death to not lose hold of her creative process, her way of transcending the ordinary. She wrote to her cousin Nora Barlow:

Anne: [It is] a matter of life and death to keep going at [my wood engraving] as much as I can and not lose hold. I feel I’ve got something in me of which I only get a millionth part, partly from lack of time and leisure of mind (by my own unregretted choice in marrying and having children), partly from things in one’s own self getting in the way and in between… Anne: [It is] a matter of life and death to keep going at [my wood engraving] as much as I can and not lose hold. I feel I’ve got something in me of which I only get a millionth part, partly from lack of time and leisure of mind (by my own unregretted choice in marrying and having children), partly from things in one’s own self getting in the way and in between…

William: Gwen’s mother, Lady Maud Darwin’s death in 1947 led to Gwen having to sort out half a century’s family papers, not least plenty of childhood letters and diaries. In 1964, two years after the death of Gwen’s brother Charles, Newnham Grange became Darwin College.

After her mother’s death, Gwen had thus plenty of reason to relive her childhood. Not only was she living a hundred yards from where she was born and grew up, but she had just illustrated two children’s books: The Runaway by Elizabeth Hart and Countess Kate by Charlotte Yonge. In October 1949 she wrote to Richard de la Mare (son of the poet Walter) at Faber and Faber:

Anne: I have long been playing with the idea of writing a sort of autobiography as a peg to hang illustrations on; and I am now taking the liberty of sending you a scrap out of it (not the beginning nor yet the end) to see if you think it would do to publish someday with lots of pictures.

I simply hate writing, and I can’t be bothered to write it, unless it’s good enough to publish. I am afraid that what I have written may be too flippant and rather odious, and I would like to know what some outside Literary person feels about it. The idea of the book is not to be a continuous autobiography, but a series of separate chapters called Sport, Religion, Art, Relations, etc. etc.

William: de la Mare’s response was immediate and positive leading Gwen to start the book she first called: Children Should be Seen and Not Heard, but later to be renamed Period Piece. She wrote to Walter that she conceived of the book…

Anne: …as a social document – to be a drawing of the world as I saw it when young, not at all as a picture of my own soul (though I suppose that gets in by mistake). The world has altered inconceivably since I was a child, when there were only horses – not even bicycles at first – and lamps and candles: and when labourers got 12s or 13s a week as a rule; – and when I simply couldn’t conceive that I could be my own cook!

William: By the autumn of 1951, when Gwen was 66, she had finished the text and most of the drawings for Period Piece (ironically she preferred drawings to wood-engravings for her own book, for their immediacy). But later that same year she had a massive stroke that paralysed her down her left side. Nevertheless the book was published on 10 October 1952 at one guinea. It was an immediate success. Letters of praise poured in and reviews were enthusiastic. The anonymous review in the TLS declared: “Mrs Raverat is not a Darwin for nothing!” In a letter to Gwen, Leonard Woolf wrote: Dear Gwen, if I may call you so. It seems a lifetime since I came with Virginia to see you in Caroline Place… I want to say with what pleasure and admiration I have read your book and also what enormous pleasure it would have given Virginia.

William: Period Piece has become one of those books that builds itself a favoured niche in the subconscious of everyone who reads it. It has been in print from Faber – albeit in editions of ever-decreasing print quality – for 61 years now. This delightful Slightly Foxed edition is a beautifully printed objet d’art of which Gwen would have thoroughly approved.

Period Piece has many qualities, not least, for members of the Darwin-Wedgwood clan, acting as a needed deflator of pretension. In her chapter on Down House, Gwen wrote:

Anne: The faint flavour of the ghost of my grandfather hung in a friendly way about the whole place, house, garden and all. Of course, we always felt embarrassed if our grandfather were mentioned, just as we did if God were spoken of. In fact, he was obviously in the same category as God and Father Christmas. Only, with our grandfather, we also felt, modestly, that we ought to disclaim any virtue of our own in having produced him. Of course it was very much to our credit, really, to own such a father; but one mustn’t be proud, or show off about it; so we blushed and were embarrassed and changed the subject. Anne: The faint flavour of the ghost of my grandfather hung in a friendly way about the whole place, house, garden and all. Of course, we always felt embarrassed if our grandfather were mentioned, just as we did if God were spoken of. In fact, he was obviously in the same category as God and Father Christmas. Only, with our grandfather, we also felt, modestly, that we ought to disclaim any virtue of our own in having produced him. Of course it was very much to our credit, really, to own such a father; but one mustn’t be proud, or show off about it; so we blushed and were embarrassed and changed the subject.

William: Gwen must have been delighted when she read a letter full of praise from Rose Macaulay, the novelist:

Anne: I can’t resist telling you (as I have already told you anonymously, in the Time Lit Sup) what an adorable book Period Piece is. I should really send you a large bill, for buying copies for people has nearly ruined me this Christmas – and I gather must have nearly ruined many people, judging by the way the copies in the bookshops melt away. It is no wonder. The book is practically perfect – funny, witty, beautifully written, more than beautifully illustrated, everything such a book can be. It made me laugh and nostalgically sigh, and laugh again, and pause to admire the aptness of the actual writing, which never puts a foot wrong… Raymond Mortimer and I were agreeing that P.P. is the most attractive book we have read for a long time. The difficulty in reviewing it was that there seemed nothing to be said against it, so one’s review necessarily lacked critical balance! Few books are like that.

William: We are here to celebrate this beautifully made edition of Period Piece and its author and illustrator, my grandmother, Gwen Raverat. That the work merits a new edition 61 years after it was first published is testament to its powers of endurance, the efficacy of Gwen’s charming wit and observation, and the lasting and happy marriage of image and text that she achieved in this book.

Gwen would never know – she died just four years after its publication – just how very popular Period Piece would become, translated as it was into Japanese and most European languages and never out of print. And yet, at the beginning, she had tentatively asked her publisher:

Anne: Does it sound like a book?

|

|